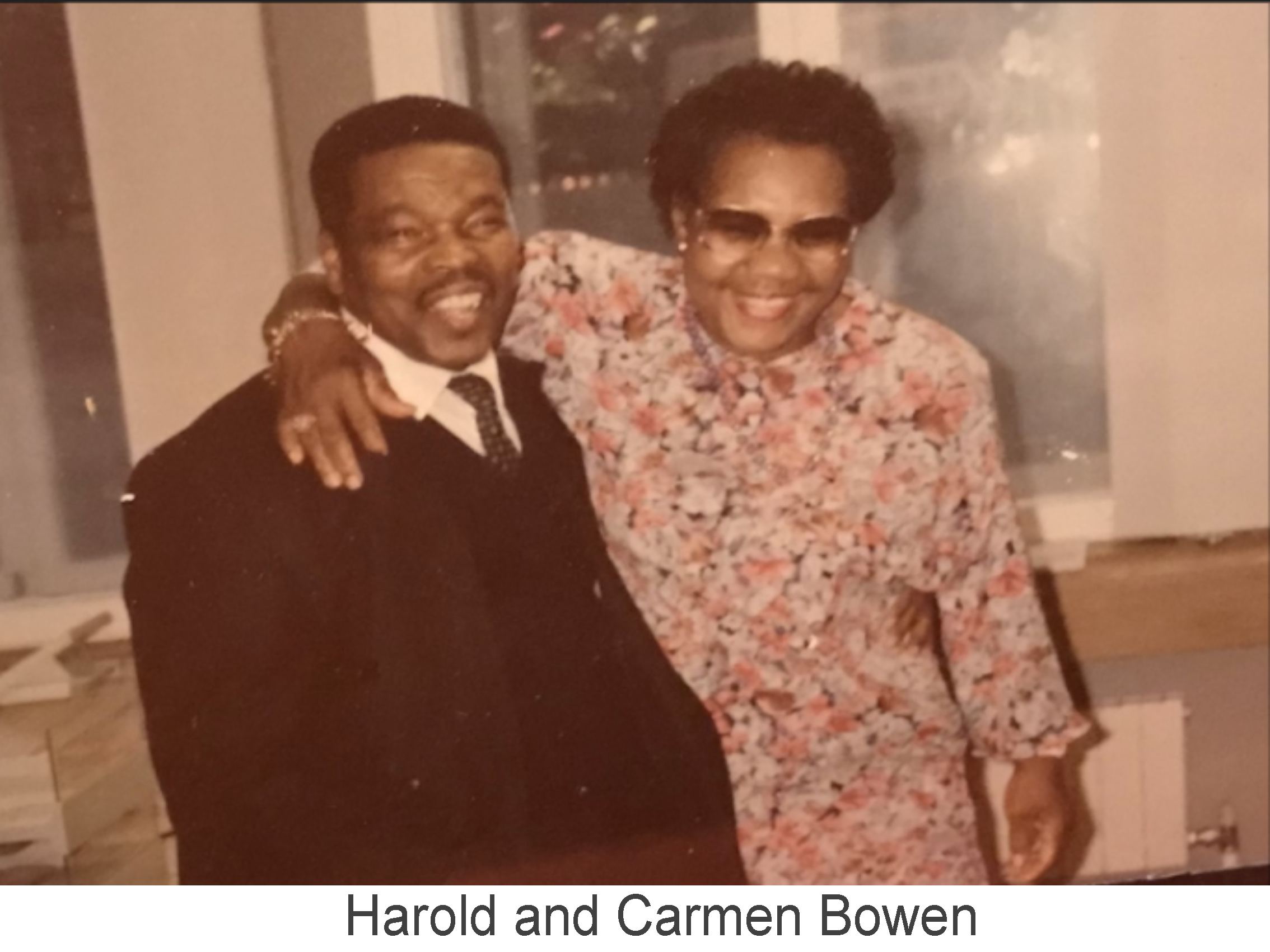

A heart-warming story of two Windrush migrants who come to England, found love, faced racism, raised a family, blended cultures and left a legacy of “making Britain”.

Harold and Carmen Bowen are two members of the Windrush generation. Both had heeded the call of Britain which required aid in the aftermath of the Second World War. Harold and Carmen migrated from Barbados and lived in Britain for over thirty years. They established lives here and their children carry on their legacy today. I spoke to Michele Bent, their daughter, to learn about their stories: why they chose to migrate, the hardships they faced and overcame, their successes and to gain insight on her perspective on the Windrush generation as a whole.

“So, she found herself getting on that boat setting sail for England.”

We start off by discussing why Michele’s parents decided to migrate to Britain. Michele begins by describing her mother’s journey. Carmen Bowen was born in a small village in St Peter, “a little village where everyone knew each other, a close-knit community.”

Michele explains that a girl in Carmen’s village would go to school until they were about sixteen. The options of work were either to labour in the cane fields or to become a seamstress; Carmen had chosen the latter. The issue became that in this small village, many other girls had also chosen the vocation, which didn’t leave a lot in the side of business.

So, when the vicar of the church that Carmen was faithfully involved in had suggested she take the opportunity to migrate to England and become a nurse, she agreed. In fact, Enoch Powell was invited to Barbados and encouraged Barbadians to come to Britain to build up the mother country. “Enoch Powell of all people, would you believe it!” she tells me with raised brows. It’s certainly a surprise.

However, the issue of raising the funds was a slightly tricky one. Michele notes that to borrow money you would have to be a landowner in possession of a Land Tax Bill. Carmen was an orphan and lived with her aunt, a greatly respected figure in the local community. So, in that tight-knit community, Carmen’s aunt was able to raise the funds needed and a family friend provided the land tax bill. Michele’s recollection reminded me of that age-old expression, how it takes a village to raise a child.

So, at the young age of nineteen, Carmen found herself docking that boat setting sail to England in 1956.

“He came by plane. I have no idea how he did that!”

Whilst Carmen had migrated for the purpose of seeking a securer vocation, Harold Bowen already had one in Barbados but decided to make his own way in Britain.

Harold grew up in the parish of St Lucy, Barbados and worked for a doctor as his “right hand man”. Michele explains that her father put on many hats, undertaking the roles of “chauffeur, maintenance, gardening” and so on. The family greatly valued the role Harold had. So much so, in fact, that when Harold had mentioned the possibility of working in Britain, the lady of the house said she would take him out of the will that had bequeathed Harold some land and money.

It seemed to have an adverse effect, as Harold was further propelled to go to Britain. I comment that Harold “Sounded like a man who does things for himself!”. “Absolutely!” Michele responds smiling.

So, Harold had chosen to migrate at the age of around twenty-five in 1955 where he joined the British Rail in London. His method of migration was quite uncommon as he migrated via a plane. How he managed to do that was both mystifying to Michele and I.

“She was in the dayroom reading a book and felt a pair of eyes boring into her. So, she looked up and said ‘What are you staring at?’ And they got talking and the rest is history.”

Harold and Carmen met after three years of living in Britain. Carmen had transferred to a different nursing home in Hampshire, after finding out that she could undertake a few qualifications she was seeking elsewhere.

It turns out that Hampshire was the place to be as Michele explains that men from London would often commute to see the women in Hampshire (at this point, there were increasing numbers of Caribbean women working as nurses). Harold decided to accompany a friend traveling to Hampshire.

Michele recalls their parent’s first interaction with a laugh but with her mother’s impression of London with a more sobered tone. In her previous places of work, Carmen and the previous few other black women nurses were treated as a “novelty.” However, when Carmen came to join Harold in London, she herself began to face the racism she had only heard about.

It is another reminder of the fact that London has not always been the welcoming, multicultural space it now boasts to be. Certainly, both Harold and Carmen’s expectation of living in Britain were quickly broken down.

“It was like they were invited to the party, and when they got there the door was shut in their face.”

I ask about what Michele’s parents’ expectations were in how they expected to be received in Britain. Michele describes how her mother had always claimed: “I know more about Britain than I know about my own country.” All that Carmen was taught in school concerned Britain and the British Isles. Michele recalls when her mother had described singing a song specially crafted for Princess Margaret on her visit to the island. Her mother described seeing Princess Margaret doing the royal wave at the Garrison Savannah.

Both Harold and Carmen felt pride in heeding to the call to work in Britain, they were proudly British as they were taught to be. Yet that was not the reception either of them came to face, as Michele notes that this was the time where the infamous posters of ‘No blacks, no dogs, no Irish’ were plastered around in public spaces. How devastating must it have felt to be rejected by people when you had an equal right to be living there, when you were actively encouraged to migrate by people from Britain.

“Once they got here and realised that was the score, Caribbeans got together.”

Nonetheless, Harold and Carmen Bowen persevered. Of course, if there is a defining characteristic of the Windrush generation, perseverance is a strong candidate. Michele explained that British-Barbadians began to group together with other islanders in that feeling of solidarity. It meant that in the face of hostility, this generation still had a community that they could depend on.

In fact, this community enabled British-Caribbeans to flourish. Michele offers the example of the ‘partner system’ where a group of people would all contribute money to a pot weekly and every so often one person would be able to take that pot and spend it on what they needed. Often this was a deposit on a house. The contributions would continue and then the next person would have their turn. To be able to form a financial support system with each other was something I found particularly inspiring, especially in a group of people who were still adjusting to a completely different environment.

“That feeling of pride in being able to go out and buy that property, that was a great moment.”

Clearly, Michele’s parents had faced many moments of hardship that they had overcome. I ask about the equally important successes they had, “What was the moment when your parents had thought ‘Yes, I have achieved something huge here’?”

Michele pauses before stating “I think it was when they were able to purchase their own house.” She describes the pride her parents felt in purchasing a house in London. Again, I see the testament to their determination to establish their lives here. Despite the hostility faced in London, Harold and Carmen had thrived to the point of purchasing a house in the same area which they would live in for over thirty years.

Michele adds that this was not the original expectation for either of her parents.

“It’s interesting, whenever you speak to a Caribbean person, they always speak of this five-year plan. They were only ever going to come here for five years. I think that once you realise you have established roots, you’re here to stay.”

Indeed, Michele shares an anecdote of when her mother lived in a shared living space. At the time, Michele’s elder brother was a small child and to take care of his needs would require putting a shilling in the gas box to turn the oven or hob on. Michele dryly comments on how the moment when her mother had put the shilling in, the kitchen would be swarmed by her fellow roommates, all who had a sudden need to use the oven or hob. It was this realisation that Carmen and Harold needed a space of their own that fuelled their search for a home they could call their own.

Certainly, I saw why Michele chose this moment as her parents’ defining achievement in Britain.

“So, we had the Caribbean food mixed with a side of British.”

We shift the conversation onto Michele’s memories of growing up in Britain, specifically on the emergence of British-Caribbean culture. She laughingly recalls a time when her fellow eight-year old classmate had suggested her household only had “‘black-people records.’” To her realisation, the classmate was correct. Michele grew up in a household that was always playing records, specifically the tunes of soul (“back then it was calypso”), reggae and R&B.

There was even a cultural fusion at the table. Sunday dinners consisted of the typical “Caribbean curry, rice and peas but then we would also have Yorkshire puddings and roast potatoes right beside it.” As a second-generation migrant, I could certainly relate to these types of dinners; witnessing a representation of your identity on a plate.

Michele also recalls how her family had made the effort to continue Barbadian traditions in Britain. In the late seventies, Michele’s cousin Pat married on a Saturday and then the following Sunday, the family congregated at her house to continue celebrations. Then the following

Saturday, the celebrations still continued: “They were celebrating for days! I remember having my bridesmaids dress and then changing into other outfits.”

Michele had only recently realised that Pat’s wedding celebrations were an effort to continue a long-standing Barbadian tradition when she spoke to her mother recently. Carmen and Harold had retired back to Barbados after living over thirty years in Britain. Michele’s father had passed away in 2009 though she notes it always “seems like yesterday.” She always makes an effort to remember his stories. Michele speaks every day to her mother through FaceTime (we delight briefly on the ability to forgo calling cards) and she recounted how her mother had told her about her own aunt’s wedding which lasted three days. Thus explaining Pat’s seemingly endless wedding celebrations.

“Their legacy here is that they made this country.”

My final questions for Michele concerned the legacy of the Windrush generation. I asked her what she would want other people to know about the Windrush generation, especially since this generation has recently entered the public consciousness and discussions continue over their legacy.

Without hesitation, Michele answers “How things were hard. Talking about how and why they came here is so important.” Michele notes that often news channel reporting would display the same images of the HMS Windrush docking and of people walking the gangplank and entering the country. Michele wants a focus on individual stories because whilst they have commonalities, they are also different and should be heard for their own worth.

Michele notes that the legacy of the Windrush generation and of all the other Commonwealth migrants is one of making Britain. She asks:

“Imagine taking out all the BAME people from the National Health Service from the 1950s till now, what would be left? The same with the transport system, the care system, the grassroots of education.” It’s a question worth asking, we can see the fruits of the labour put in by the Windrush generation and other Commonwealth migrants today, and people from those nations continue to support these vital institutions.

I left that conversation with Michele with a profound sense of appreciation and awe for her parents and of the Windrush generation. Our conversation only reaffirmed the importance of telling those individual stories that allow us to appreciate the struggles and successes of a generation that had given so much to Britain. It is in telling these stories that we are reminded of that irrevocable truth that Michele and I concluded on:

“So, it really is the foundations of this nation that they’ve built.” This time it’s not a question I’m asking Michele to clarify. “Absolutely,” she responds with conviction. “It’s the foundations.”

If you have been inspired to learn more about the journeys made by some of the Windrush generation, here are some links provided as a suggestion point:

https://www.bl.uk/windrush/articles/floella-benjamin-on-coming-to-england

https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/listening-london-and-windrush-generation